Every couple of months, flashy new hardbacks come out with accounts of being mind-blowing! eye-opening! life-changing! etc, etc. Last summer, the book of the moment was Sarah Thankam Mathew’s All This Could Be Different (which I disliked), and earlier this year it was Maggie Millner’s Couplets (which I admired). As much as I try to resist the overzealous praise coiling ’round each season’s new releases, contemporary literature is my sport of choice and I enjoy participating in its culture which naturally involves buying an abundance of books (or at least, this is what I tell myself). Nonetheless, it is wise—generally and financially—to avoid scooping up each title that critics and TikTokers deem the latest best read, especially given how much of this hype is orchestrated by behind-the-scenes publicity and marketing campaigns. Spending $30 on a buzzy book can be thrilling until you realize that it is indeed just fine, which, of course, is the case for most books. But I’m feeble, unrepentant, and too impatient to wait for library holds.

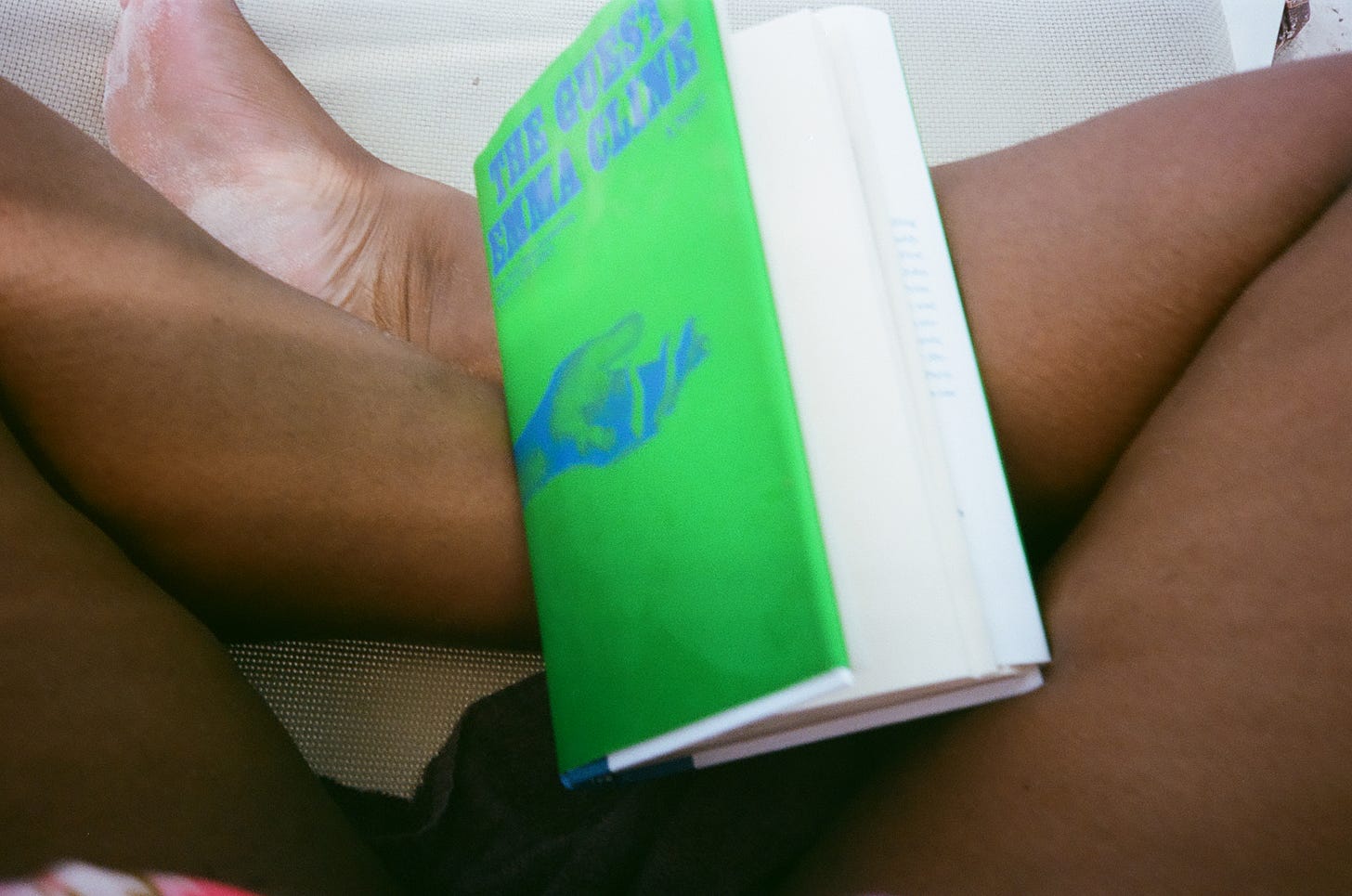

A few weeks ago, I found myself in a cramped fiction aisle, awkwardly asquat, ruminating on purchasing the open-faced text kissing my thumbs. It was likely my third or fourth bookstore visit that month, and therefore my third or fourth time breaching a self-imposed bookstore ban. On this particular afternoon, the novel in question was Emma Cline’s latest work, The Guest. Described as a propulsive literary thriller set in Long Island, this story has quickly become the book of the season, making nonstop appearances on newsfeeds and social media timelines across cyberspace. The buzz of Cline’s previous works, Daddy and The Girls, didn’t capture me upon their release. But this one—with its eye-catching, lime green cover and touted reputation—tempted me all summer. Before my eventual purchase, I had flipped through the novel on several, different occasions in several, different bookstores without feeling much conviction. I’d pick it up, read the introductory pages, and maybe even stroll through the shop with it in my hand before putting it back on the shelf. Yet, each time I abandoned the book, I’d experience a mild curiosity that fluttered when I scrolled past a raving review or spotted it amongst passersby. Looking back, it was obvious that I was going to cave.

From the start of the story, readers are ushered into the inner world of Alex, a 22-year-old woman spending the summer with her much older boyfriend, Simon. As the protagonist sets the scene—a “heaven[ly]” beach town full of moneyed somebodies—her recent past life is slowly revealed. Before meeting Simon, Alex worked as an escort in New York City and lived with roommates, but given her frequent tendency to skip rent payments and pocket other people’s belongings, her roommates kicked her out. Lucky for her, she’s able to live with Simon (who is completely unaware of her living situation and her line of work) and push this misfortune to the back of her mind—well, at least for a little while. Eventually, after a few tactless decisions, Alex is booted from Simon’s home and forced to confront her disheveled relationships and subsequent homelessness. But when the time comes for her to do so, she enmeshes herself with strangers and spends a week drifting through the Hamptons-like town, making increasingly alarming choices as the narrative goes on.

With its notably unlikeable main character, The Guest is the latest rendition of novels that explores the psyche of an unhinged woman reckoning with the modern world. Bookseller and content creator, CJ Alberts calls this specific niche of literary fiction “Depressed Woman Moving” or DWM. And in this case, with Cline’s detached narrator literally moving from one uncertain situation to the next, DWM couldn’t be a more accurate label.

In an interview with NPR’s All Things Considered, Cline states: “I resist some of the classical narratives in a book or a movie that the character should learn something by the end, that there should be a moral because I find life is so often not like that. I find that people often don't change. There isn't a moral to a lot of our experiences. And it really came down to this is going to be like a character study.”

As sharp as Alex may seem at first, it becomes clear that she is a rather lousy person who leads a life stirred by the compass of her delusions, and it is admittedly entertaining to witness how she navigates the situations she glides into. But at a certain point, after the main character’s third or so scheme, the story starts to feel rather formulaic and redundant, as if Cline became entranced by her own authorial tricks and wanted to see them again and again. With a character as stressful as Alex, it makes sense that the reading experience would eventually become exhausting. We all know someone whose chaotic lifestyle can go from being amusing to draining in a short span of time. Alex’s drifts were damned to be exasperating, and that’s partially what makes the novel engaging. However, after the second half, Cline resorts to rather predictable scene transitions that her well-written sentences do not conceal. By the conclusion, all of the story’s magnetism and build-up are stilted by a lackluster finale. I closed the book feeling as if the final payoff was smooshed, like a near orgasm that tragically gets out of reach.

Reviewers keep calling The Guest the perfect beach read. And I’ve come to agree with that. It’s fast-paced, voraciously readable, and it provides much to talk about, making for an ideal seaside companion. But in terms of what it has to say about the vaguely explored topics—class, labor, and sex work—it falls flat. As writer Sarah Rose Etter keenly points out, “If Alex is a sex worker, why do we never see her engaged in actual sex work? If this is a core part of her life, if it is a driving part of her motivations, if it has blown up her life to this extent, why do we look away from this part of her as a character? […] By avoiding this part of Alex’s life, the central conflict of the novel—The Outsider vs. The Rich—becomes toothless. She ends up just as vapid, opportunist, and as aimless as the wealthy around her.”

Emma Cline seemingly set out to create an atmospheric, character-focused piece of fiction, and sure she succeeded at that. But, by avoiding further probe into the book’s themes, Cline renders an aesthetically pleasing but ultimately reductive image that uses sex work and class as decorative tools to frame the main character’s bad behavior. I should’ve waited for the library’s copy.